‘Honest John’ McGowan combined farming, business, politics

The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

He died over 100 years ago, and is now almost forgotten, but in his day John McGowan was a household name across Wellington County. His career began on the family farm, and took him into several business ventures, and to seats in the provincial and federal parliaments.

John McGowan was born in Greenock, Scotland, in 1845. His father, Duncan McGowan, worked in the shipping business, owning several ships in the coastal trade in Scotland. From modest beginnings he became prosperous. For reasons that are not entirely certain, Duncan McGowan decided to change occupations. He sold out his shipping business at a great profit and, in 1857, with his wife and 12-year-old John, he migrated to Kingston, Ontario, and then to Guelph.

A short time later, the senior McGowan purchased a 285-acre farm a stone’s throw northeast of Alma, on Concession 15, Lots 22 and 23 of Peel. He had sufficient funds to hire men to clear and work the farm. The good grain markets of the 1860s and early 1870s, combined with the large acreage he had under cultivation, earned him a good profit. Duncan McGowan was one of the first prosperous farmers of Peel.

Young John assisted on the farm, and eventually took over management of it. But he had an eye on politics as well. Much to the chagrin of his father, who was a lifelong Liberal, the North Wellington Conservatives in 1874 nominated 29-year-old John as their candidate for the provincial legislature. His opponent was E.J. O’Callaghan of Arthur.

The campaign took on a religious character. Orangemen, anxious for the defeat of O’Callaghan, supported McGowan, though he tried to distance himself from them. McGowan won by 60 votes, bucking the trend that saw Liberals elected elsewhere. McGowan won the subsequent election, but was unseated for electoral irregularities. He chose not to stand again. He had grown weary of the animosity of politics, and the home farm required more of his attention when his father’s health deteriorated.

Duncan McGowan died in 1879. The farm and other assets passed to John. Among these was an interest in the flax mill at Aboyne, on the south side of the river between Fergus and Elora.

Duncan had loaned money to the operator of the mill, James Henneberry, in 1870. When the mill ran into financial problems in 1872, McGowan took title to it. Both the McGowans rented it out on annual leases through the 1870s and 1880s.

A year after his father died, John McGowan married Margaret Hawley. The couple eventually produced eight children. John’s political interests continued. He gained a seat at the Peel council table, later serving as deputy reeve, and as reeve between 1883 and 1886.

During the 1880s, McGowan became increasingly interested in the flax business. In 1887 he established a plant at Arthur to process flax fibre and extract the seeds, which were becoming increasingly valuable as a source of oil. Not only was it a major ingredient of paint, but it was a basic ingredient for new synthetic products that reached consumers as linoleum and oilcloth.

Around 1890, McGowan began operating the Aboyne mill himself, rather than renting it out. He installed equipment to extract the linseed oil from the flax seeds, which were shipped down from the Alma plant. He also sold the residue, in the form of oilcake, as cattle feed.

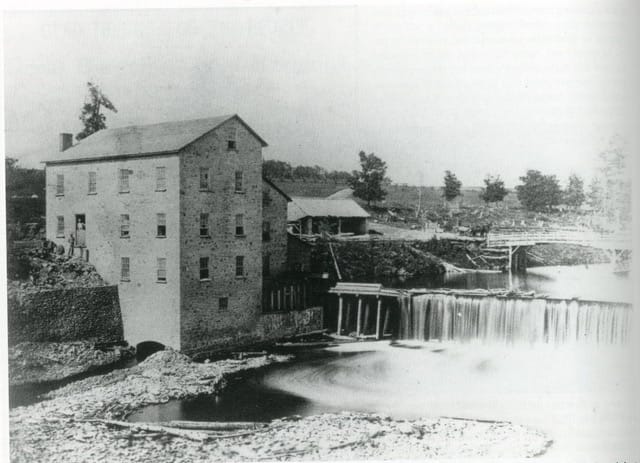

Meanwhile, the Aboyne flour mill, on the north side of the river, ceased operation in 1884. With the equipment removed, the building, aided by fire and vandalism, was soon reduced to a ruin, and flood waters swept away the dam. McGowan purchased the property in 1896 for $125.

McGowan planned to scale up his production considerably. He hired Udney Richardson, an Elora contractor and future owner of the Elora Mill, to construct a new dam of timber for $1,750. Another contractor rebuilt the flour mill as a four-storey structure, containing new equipment for the extraction and processing of linseed oil.

Local farmers showed a renewed interest in flax in the 1890s. Several Elora businessmen involved themselves in the flax business. Furniture maker John C. Mundell, for example, processed flax in several locations in Elora through the 1890s. He sold the seed to McGowan, and used the fibre for packing material for his furniture.

McGowan completed his construction work in 1899. His next project was to build a 0.75-mile railway siding to the mill from the Canadian Pacific line at the eastern edge of Elora. This permitted him to bring in large supplies of flax seed, and to export his linseed oil and oilcake. By the standards of the day, McGowan’s linseed oil mill ranked as a major industry, with a significant impact on the agricultural economy.

In November of 1902, for example, he purchased 80,000 bushels of flax seed at $1.25 per bushel. At full capacity, the mill could produce 35 50-gallon barrels of linseed oil and 15 tons of oil cake each day, when it was running 24 hours. This production required between 600 and 1,000 bushels of flax seed daily. The operation employed about 25 men. Much of the output was exported to Great Britain.

McGowan’s political career went into eclipse after he left the reeve’s chair in 1886. The flax business required much of his energy. In public, McGowan liked to present himself as a farmer. He took great pride in his acreage and his prize-winning cattle.

Though he was not a typical farmer, McGowan was swept up in the farm movement of the 1890s, siding with agrarians in their demands for higher commodity prices and a greater voice for farmers in politics. McGowan feared the rise of big conglomerates and cartels, which he viewed as a threat to small manufacturers and to farmers.

In the mid 1890s, McGowan drifted from his Conservative base to a flirtation with the new farmers’ party, the Patrons of Industry. He considered running federally in Wellington Centre under that banner in the 1896 election. Both friend and foe recognized that he would be a likely winner. The Conservatives also offered him the nomination that year. He turned them down.

Four years later, when the farmers’ movement had died down, John McGowan accepted the Conservative nomination. During the 1890s he had picked up the nickname “Honest John,” and he ran under this banner. McGowan’s popularity as a champion of farmers and of small-town life drew sufficient support from the incumbent, Andrew Semple, to give McGowan the victory.

The year following the election, McGowan moved from his farm to Elora. He purchased the Mill Street estate of the late Judge George Drew from his widow for $1,750, and spent an additional sum making improvements to the property.

Another reason for moving to Elora was to be closer to his newest venture: the Wellington Dressed Meat and Cold Storage Co. McGowan was the largest shareholder in this venture, which would produce beef and pork products from a new facility to be located on the western edge of Fergus.

He sat as the founding president of the firm, with a board that included leading farmers from the area and four Fergus businessmen. It proved to be a disappointment: production was slow to commence and a series of misfortunes plagued the business. The building eventually became the home of Superior Barn Equipment.

McGowan still owned the Alma Flax and Chopping Mill. While he was in Ottawa, his son John McGowan Jr. managed both the Alma and Aboyne operations. Another son, Charles, was with the business briefly, then established a shoe store in Elora. His third son, Duncan, had been killed at 15 in a hunting accident in 1899.

The future of the flax business, and the trend to consolidation, caused McGowan much anxiety. In 1903, with much reluctance, he took his mill into the new Dominion Linseed Oil Co., a combination of mills at Baden, Owen Sound, Guelph, Montreal and his own at Elora. The Livingston interests of Baden dominated the firm, but McGowan served as vice president, a position he held until his death. He explained that he would rather see the Aboyne mill operating as part of a larger firm than to see it squeezed out of the market by aggressive competitors.

McGowan ran again for a federal seat in 1904. His old riding of Wellington Centre had been abolished. He lost narrowly in the expanded Wellington North seat, as the Laurier Liberals were swept back into office. Leaders of the Conservative Party had not warmed to him. As an MP he did not hesitate to break with his own party when his own beliefs differed from the party line.

Removed from day-to-day management duties at his mill, McGowan went back to his farm in 1904, but soon returned to Elora. He received an appointment as police magistrate, and he took his duties seriously, building on the reputation he had built for fairness and honesty.

McGowan’s Elora friends pressured him to try for a seat at Elora council. He declined at least three times, but finally bowed to the pressure. Elora voters elected him in 1912, 1913 and 1914.

McGowan greatly admired Adam Beck and his plan to electrify small-town and rural Ontario. He campaigned to bring Ontario Hydro to Elora, and served as the first chairman of the Elora Hydro Commission.

The Dominion Linseed Oil Co. continued to operate the Aboyne mill until 1915, under John McGowan Jr.’s management. Several factors conspired against the mill.

The plant was small and increasingly inefficient in comparison to others in the industry, and survived only until 1915 because of the policies of the company. Falling prices were encouraging local farmers to move to other crops. And a local labour shortage developed in 1915, with many able-bodied men in the army. When the Aboyne mill closed in 1915, John McGowan repurchased it from the Dominion Linseed Oil Co. A rumour that John C. Mundell would build a new furniture factory on the property persisted for several years, but nothing concrete materialized.

John McGowan died at his Mill Street home (known today as the Drew House Bed and Breakfast) on Oct. 20, 1922 at the age of 77.

He had been ill for about four years, and took pleasure and comfort in the steady stream of old employees and business contacts who came to wish him well in his last months. Irvine Lodge, where he had been a member since 1868, provided a Masonic funeral.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Nov. 15, 2002.